OKLAHOMA CITY (BP) – Although Oklahoma City police chaplains Jack and Phyllis Poe weren’t inside the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building when a truck bomb exploded at 9:02 a.m. on April 19, 1995, the aftereffects of the tragedy pushed them to grapple with forgiveness.

“One of the things we really didn’t understand is, as caregivers, we want to make a difference, but we didn’t realize that you can give yourselves away. And, Phyllis and I gave ourselves away,” Poe said, reminiscing about the tragedy as its 20th anniversary approached.

“The two weeks before it happened, we had [attended] seven funerals,” Phyllis recalled. “We were in the office and I started crying. I said, ‘God, please, no more funerals, we can’t do this, we’re too tired.’ So, we were spent before we ever got to the bombing.”

On April 19, they were getting dressed to go to yet another funeral when the bomb went off. “Our house was 8.5 miles away,” Jack said. “I thought something in our house had exploded. Then I thought an airplane crash had caused that massive boom.

“So, I went to the car and checked our [police] radio and finally someone said they thought it was the federal building downtown.

“I left, and Phyllis said she would follow me later. I pulled in behind one of our [police] units and followed him downtown.”

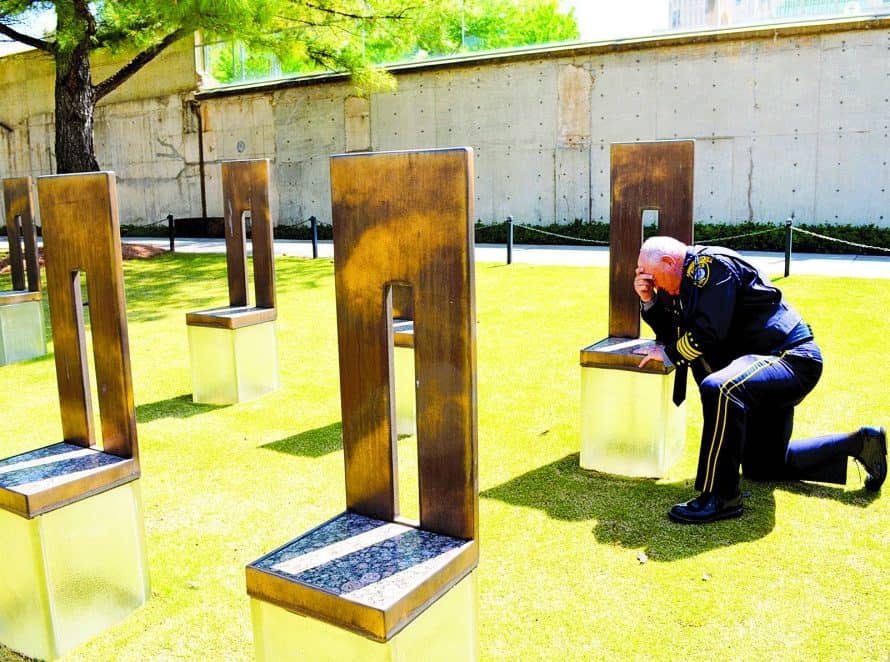

The Poes would spend the next 21 days at the bomb site. They worked tirelessly in the weeks, months and years after the bombing, pouring their hearts and souls into the lives of others. The smiles on their faces and the ubiquitous hugging, however, masked the struggle to forgive the perpetrators of the bombing, eventually leading to an unstable marriage.

“I didn’t know where to put my anger,” Phyllis said. “I had a lot of anger. Anger that people were hurt; that people died. Anger that our lives were changed within seconds, because you’ll never be the same. No matter where we go, what we do, we talk about the bombing. It comes up somehow. Before the bombing, after the bombing. It’s one of those markers in your life.”

“Finally, we were going to a survivors’ meeting at the state capitol one night, and I didn’t want to go and said, ‘I just feel like the first person who asks me for another hug, I’d just as soon slap them.’ I knew then I was in trouble, because I love people and I’m a hugger.

Jack also struggled with forgiveness “because I didn’t like [convicted bomber Timothy] McVeigh and I didn’t like [co-conspirator Terry] Nichols.” At a church service in Texas during a break in Nichols’ trial in 1999, the preacher was speaking on forgiveness. He mentioned the bombing and McVeigh and Nichols, “and he said if they had repented, God would forgive them. I got up and walked out,” Jack said.

“I sat outside and my 15-year-old grandson came out and knew something was going on. He came out and just let me cry on his shoulder.

“I finally had to come to the realization that forgiveness is not for McVeigh or Nichols, it’s for us. Booker T. Washington, I think it was, once said, ‘I’ll never permit a man to reduce me to hate, for the moment I hate him, I become his slave.’

Forgiveness “would allow me to minister to those who haven’t forgiven,” Jack said. “And I knew that if I didn’t let it go, it would continue to eat at me.”

Things came to a head in 1999, and the Poes’ marriage was “saved” by Joe Williams, the Baptist General Convention of Oklahoma’s chaplaincy and community services specialist and a chaplain with the FBI, who arranged for the couple to attend a seminar in Florida.

“Joe came to the house and had airplane tickets to Florida for us to go see Charles Figley,” Phyllis said of a leading specialist for emotionally traumatized people.

“We thought we were going to a big conference on something called Compassion Fatigue. But, when we got there, the conference was just the two of us.

“Joe, along with the Lord, saved our marriage by coming over and loving us.”