HANNIBAL – Eva Mozes Kor doesn’t mind talking about the nine months she and her twin sister spent in Auschwitz during World War II. She openly shares about inhumane experiments by infamous Dr. Josef Mengele. She matter-of-factly tells of watching as other Jewish children were shot as the Allies drew closer to the concentration camp. But, all things considered, she’d prefer to talk about forgiveness.

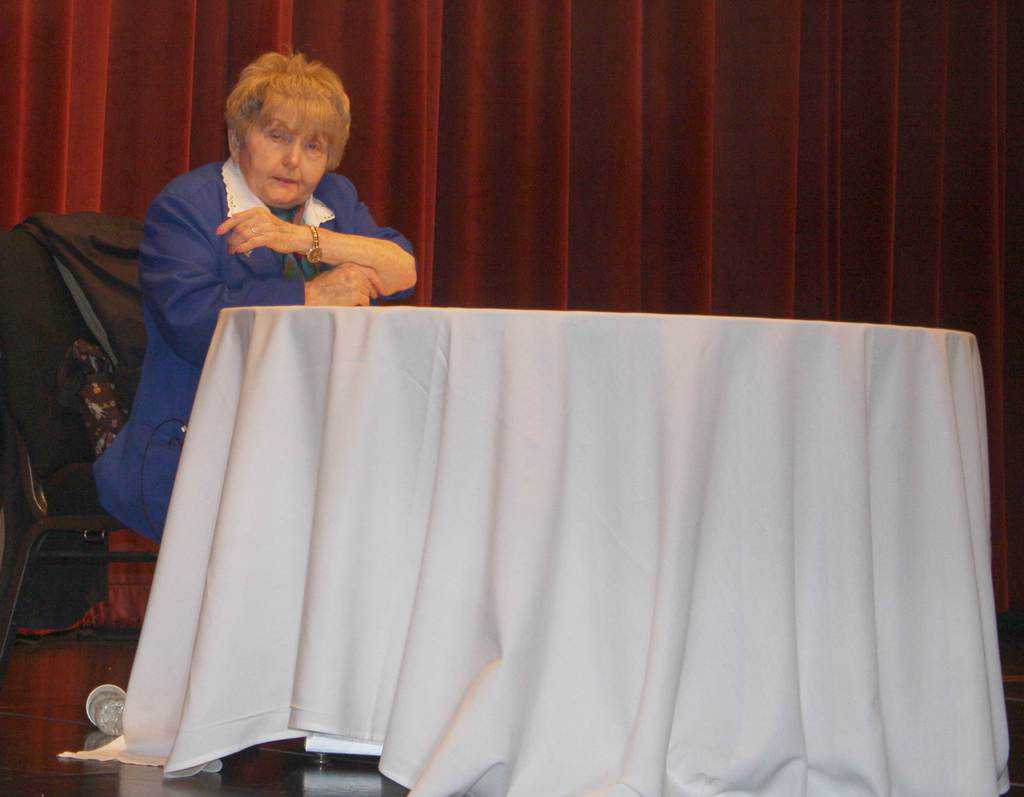

Kor spoke for nearly two hours at Hannibal-LaGrange University March 28 to a packed house of students and the community, later answering questions and signing autographs.

“It was a lovely spring day in 1944,” she began, jumping right into her story as she sat behind a small table on the large, empty stage. “Our cattle car train came to a sudden stop. I could hear a lot of German voices outside. Inside the cattle car, we were packed like sardines. We could see nothing. There was a little patch of grey sky in the corner.”

Eva was born into the only Jewish family in a small village in Transylvania. When she was six years old, Hungarian Nazis occupied the village and in 1944 they were loaded into that cattle car and taken to Auschwitz. After four days on the train hours without food and water, Eva and her family were let onto the selection platform at the camp along with hundreds of other Jews.

“I will always remember that platform,” she said. “There’s not another strip of land like that anywhere on the face of this earth.”

Though she was still with her mother and identical twin sister, Miriam, her two older sisters and her father were already gone, never to be seen again. Nazi soldiers were combing through the crowds looking for twin children and Eva’s mother, guessing that being twins might offer some small bit of protection or special treatment from the danger, pointed Eva and Miriam out to the guards.

“One Nazi pulled my mother in one direction, and we were pulled in other direction,” she said. “We were crying. She was crying. I never said goodbye to her, but I never realized that this was the last time I would see her.”

Eva and Miriam became part of 1,500 sets of young, Jewish twins used in bizarre, inhumane and torturous experiment at the hand of Nazi doctor Josef Mengele, who thought twins held some genetic secret to be unlocked. They lived in rat-infested bunks stacked three high, and ate only coffee and bits of moldy bread. Most would die, either from the conditions or experiments.

“If you look at my tattoo on my arm, you might think it is faded,” she said. “It is not faded. I fought the guards so hard they never were able to complete it. It took four of them to hold me down. I don’t remember it – I hadn’t slept in days – but my sister said I bit one them.”

She and Miriam were at Auschwitz for nine months, enduring daily experiments. Some of the more heinous stories tell of cross-type blood transfusions, sterilization and attempting to join separate twins together as conjoined twins. Eva said she has blocked out most details of the experiments from her memory, but offered one chilling account.

“I came down with a fever and was taken to the hospital,” she said. “Dr. Mengele examined me and said ‘It’s a pity that she is so young. She will die within two weeks.’”

They left her with no treatment for a month, leaving her to crawl across the room to get food and water.

“‘I am not dead,’” Eva told herself. “‘I refuse to die. I am going to outsmart those doctors, prove Dr. Mengele wrong and get out of here alive.’”

Her fever broke and she made it back to her sister, but Miriam looked just as bad as Eva. She later discovered that when the Nazis were certain Eva would die, they considered Miriam expendable since she no longer had a twin. Miriam was thrown into isolation and subjected to kidney poisoning which would eventually contribute to her death in 1993.

Toward the end of 1944, the experiments’ frequency lessened and sightings of Allied planes overhead increased. The guards abandoned their posts as the Soviet Army closed in, leaving the children and other prisoners to starve to death. Less than 200 of the 3,000 twins brought to the camps were rescued Jan. 27, 1945.

Eva and Miriam bounced around different refugee camps before returning to Transylvania. Though she was free from the Nazis, the teenaged Eva felt stifled by the Communists in post-war Eastern Europe.

“I was a difficult prisoner for the Nazis, but I was just as bad a communist,” she joked.

The pair secured visas to immigrate to Israel where Eva went to agricultural degree and achieved the rank of Sergeant Major in the Israeli Army. She met an American tourist vacationing in Israel, also a Holocaust survivor, and the two were married in 1960. She soon followed him to America (he chose to live in Terra Haute, Ind. because it was the hometown of the first soldier he spoke to when his camp was liberated).

At the request of documentary filmmakers, she traveled to Germany in 1995 and met with Dr. Munch, an aging Auschwitz doctor, though not one that had any dealings with her (Mengele fled to South America after the war and drowned after having a stroke while swimming in 1979.)

“Surprisingly, he was very kind to me,” Eva said. “Even more surprising, I found out I liked him.”

He filled in some information about the death camps that Eva had been missing, and agreed to speak on camera for the documentary. She asked him to sign an affidavit documenting how he would sign a single death certificate for the thousands of Jews crammed into the gas chambers to be murdered.

“I was so glad that I would have an original document signed by a Nazi – a participator, not a survivor and not a liberator – to add to the historical collection, ” she said. “I was so grateful that Dr. Munch was willing to come with me to Auschwitz and sign that document about the operation of the gas chambers, and I wanted to thank him. But what does one give a Nazi doctor? How can one thank a Nazi doctor?”

“I finally thought: How about a simply letter of forgiveness? From me to him.”

“Immediately I felt that a burden of pain had been lifted from my shoulders, a pain I had lived with for fifty years: I was no longer a victim of Auschwitz, no longer a victim of my tragic past. I was free.”