“The King is a mortal man, and not God. Therefore, he has no power over the souls of his subjects; he has no power to make laws for their souls; he has no power to set spiritual Lords over them. If the King did have such authority, then he would be an immortal God and not mortal man. O King, do not be seduced to sin against God nor against your poor subjects by making such laws.”

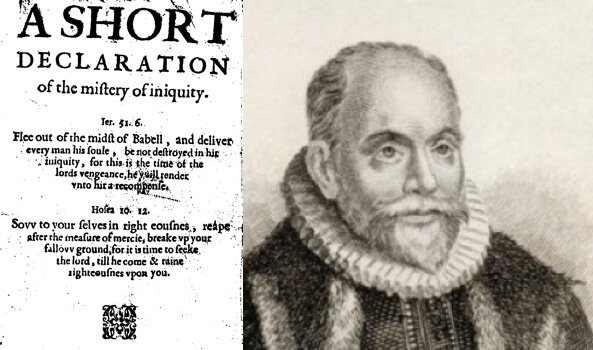

So reads the inscription in the front of Thomas Helwys’ A Short Declaration of the Mystery of Iniquity (1612).[1] Helwys’ plea for freedom of conscience and religious liberty was dedicated to King James I (1603-1625). The king, a strong believer of the monarch’s right to rule his subjects in religious matters, was not amused. Helwys soon landed in Newgate Prison where he died in 1616.

Thomas Helwys is widely regarded as the founding pastor of the first Baptist church on English soil, established in north London the same year he published A Short Declaration. A part of one of the earliest Baptist groups, his views on religious liberty reflect those of his coreligionists. The First London Confession (1644), one of the first Particular Baptist confessions, asserts that while loyal subjects should submit to secular authority, that submission does not extend to “ecclesiastical laws” which violate their religious convictions. The Standard Confession (1660) of the General Baptists put the matter more starkly in Article 24, declaring that it was God’s will “that all men should have the free liberty of their own consciences in matters of religion, or worship, without the least oppression, or persecution… and for any in Authority otherwise to act… is expressly contrary to the mind of Christ.” Article 25 made it clear that Baptists, like Peter and John in Acts 5, were not bound to obey secular authorities in matters of religious conscience and thus would not. In an era when virtually everyone believed that religious conformity was necessary for order and unity, these Baptist positions were considered recipes for chaos and anarchy.

Alongside their own liberties, Baptists defended the rights of conscience for others—even those with whom they disagreed. Helwys, for example, insisted that even Jews, Turks (i.e. Muslims), and heretics could not justly be compelled by the state in religious matters. Roger Williams (1603-1683), who founded the colony of Rhode Island, articulated the Baptist position well. Even if in the majority, Baptists should not use the power of the state to compel others in religious matters because any sort of coercion in religion—no matter how mild—violated a person’s conscience. Further, coercion also cast doubt on claims of conversion. Who knew whether a person was authentically converted or simply claiming to be so for the benefits the state allowed “Christians?” For these reasons, Williams intentionally allowed religious groups with whom he vehemently disagreed to settle in Rhode Island Colony.

Following the Revolutionary War, Baptists in America nearly universally supported freedom of conscience and religious liberty. Baptists in Virginia built a diverse coalition that promised to derail the process of ratifying the Constitution until they secured a promise that the forthcoming Bill of Rights would guarantee freedom of religion in the new republic. As the Danbury Baptists of Connecticut wrote to President Jefferson in 1801, these were not rights granted by the state “as a favor” but “inalienable rights” given by God. At the federal level, the new country had embraced that perspective. By 1833, all the states had followed suit. Religious liberty was firmly ensconced in American laws and American thinking.

Believing that the Bible teaches individuals are personally accountable before God, Baptists throughout history have vehemently supported the rights of men and women to freely choose in matters of religion, opposing state interference or compulsion. Consistent with Article 17 of the Baptist Faith & Message (2000), let us continue in their footsteps at a time when that liberty is in peril—not just for us, but for all peoples.

Note

[1] I have modernized and abridged the inscription for readability.