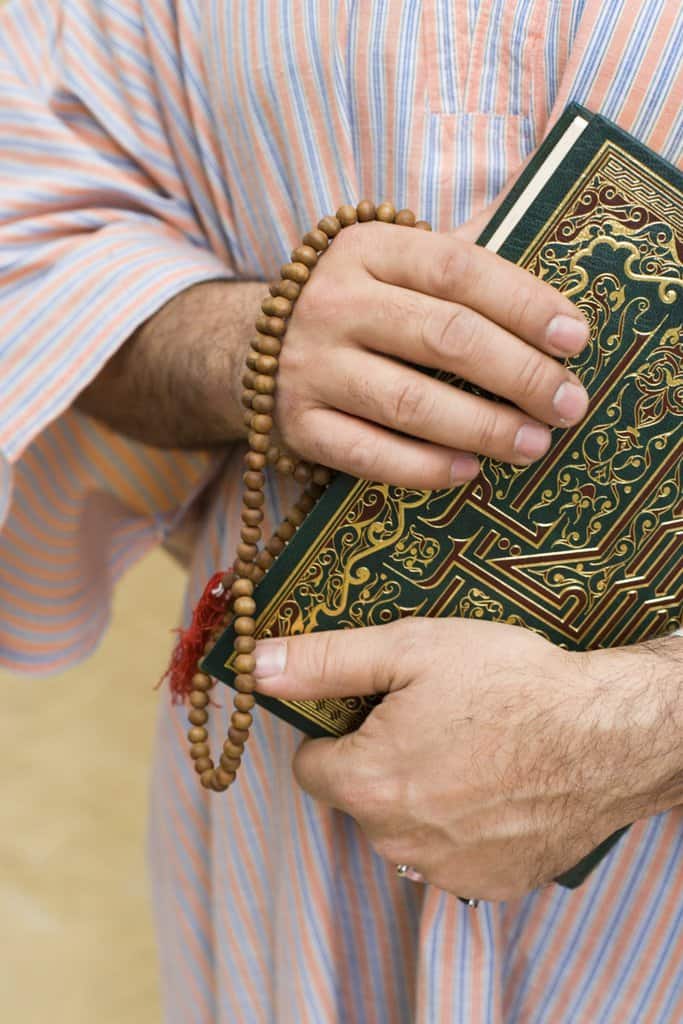

The Qur’an is Islam’s most holy book. While Muslims believe Allah has revealed many written works, including the Old and New Testaments, these revelations ended with the Qur’an, which supersedes all others.

For all practical purposes, Muslims accept only the Qur’an as the Word of God. They believe Jews and Christians have corrupted Allah’s earlier revelations in the Bible, although they honor the writings of Moses, who was given the Tawrat (Torah); David, the Zabur (his Psalms); and Jesus, the Injil (Gospel).

Where the Qur’an and the Bible disagree with one another, Muslims embrace the Qur’an as true and reject the Bible as tainted.

But what happens when the Qur’an contradicts the Qur’an, as it sometimes does?

A brief look at history and the doctrine of “abrogation” sheds light on the Muslim view of divine revelation.

Mecca and Medina

According to Islamic sources, Muhammad received his first revelation in Mecca in 610 A.D. As the angel Gabriel delivered the messages, Muhammad committed them to memory and began preaching a new brand of monotheism to his polytheistic countrymen.

These early “Meccan” passages mostly were peaceful and religious in tone. “Let there be no compulsion in religion,” urges Surah 2:256. Further, Jews and Christians are called “people of the book,” meaning they are recipients of Allah’s earlier revelations.

But something changed when Muhammad fled for Medina a decade later. Bill Warner, in The Life of Muhammad, explains: “He preached the religion of Islam for 13 years in Mecca and garnered 150 followers. He was forced to move to Medina and became a politician and warrior. During the last nine years of his life, he was involved in an event of violence on the average of every six weeks. When he died, every Arab was a Muslim. [Muhammad] succeeded through politics, not religion.”

The later “Medinan” passages, sometimes called the “second Qur’an,” bear evidence of this change. Jews are compared to apes and pigs (2:65; 5:60; 7:166), while those who believe in Jesus as the Son of God are cursed (9:30).

After Muhammad’s death, his followers compiled the Meccan and Medinan recitations into a single, unified volume. The Qur’an is organized into 114 surahs, or chapters, from the longest to the shortest. The absence of context and chronology makes understanding the Qur’an difficult unless read with the Sunna, consisting of the Sira (Muhammad’s life) and the Hadith (a collection of Muhammad’s words and deeds).

Even so, when Muslims read the Qur’an and come to conflicting passages, how are they resolved?

Abrogation to the rescue

The answer is the Muslim doctrine of abrogation. This simply means that when two passages contradict, the more recent passage “abrogates,” or overrides, the earlier one.

But this doctrine creates more problems than it solves. For example, one verse in the Qur’an affirms the doctrine of abrogation (2:106), but an earlier verse says, “No change can there be in the words of God” (10:64).

A second, and larger, problem is that the Medinan passages promote hatred of and violence toward non-Muslims, particularly Jews and Christians. One could argue that those persecuting “kafirs,” or infidels, in Islamic states are true believers, while those living in peaceful coexistence are less faithful to the cause.

Some Muslims may respond by saying the Bible also promotes abrogation. For example, the Law of Moses commands an adulterer to be stoned (Lev. 20:10). Yet Jesus sets free a woman caught in the very act (John 8:2-11).

The answer lies in the nature of Scripture. Unlike the Qur’an, the Bible is God’s progressive revelation. Each verse, chapter, and book builds upon the others until we have the complete written revelation of God in the 66 books of the Christian canon.

Difficult passages, which some mistakenly call contradictions, are resolved when we consider context, genre, purpose, perspective, and sense (literal vs. figurative language).

As for the adultery issue cited above, Paul Copan provides insight in his book, Is God a Moral Monster? “The law of Moses is not eternal and unchanging … . Old Testament sages and seers themselves announced that the law of Moses was intentionally temporary … . So let’s not think that we’re talking about the universal application of all Old Testament laws for post-Old Testament times.”

Jesus could uphold the Law and forgive the woman caught in adultery because He understood the Law’s true intent – to be our guardian until Christ so that we may be justified by faith (Gal. 3:24).

As the Creator, Sustainer, and Savior of the world, Jesus has the sovereign authority to forgive sins because He is sin’s remedy – which the two Qur’ans tragically deny.