LONDON, England – Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol is a ghost story. Sure, it’s a beloved yuletide tradition, but it’s still a ghost story – and at times a frightening one!

Despite that, it’s easy to see why it’s so popular. The book is an easy (and humorous!) read, even for those who say the “classics” aren’t for them. It’s been adapted on screen more times than I can count (I’m particularly fond of the 1992 Muppets version starring Michael Caine as Scrooge). After all, it’s an allegory of redemption by a man chained by his own greed and sin. Who can’t relate?

Consider Ebenezer Scrooge, the protagonist (antagonist?) of A Christmas Carol. Scrooge is so singularly greedy and miserly, that the character’s name has become synonymous with those attributes. He is constantly amazed that others are joyful in their poverty, even as he is terribly miserable with his own wealth as his idol. He’s described as loving darkness and hating the light, only learning of his shortcomings through a warning by his late partner, Jacob Marley.

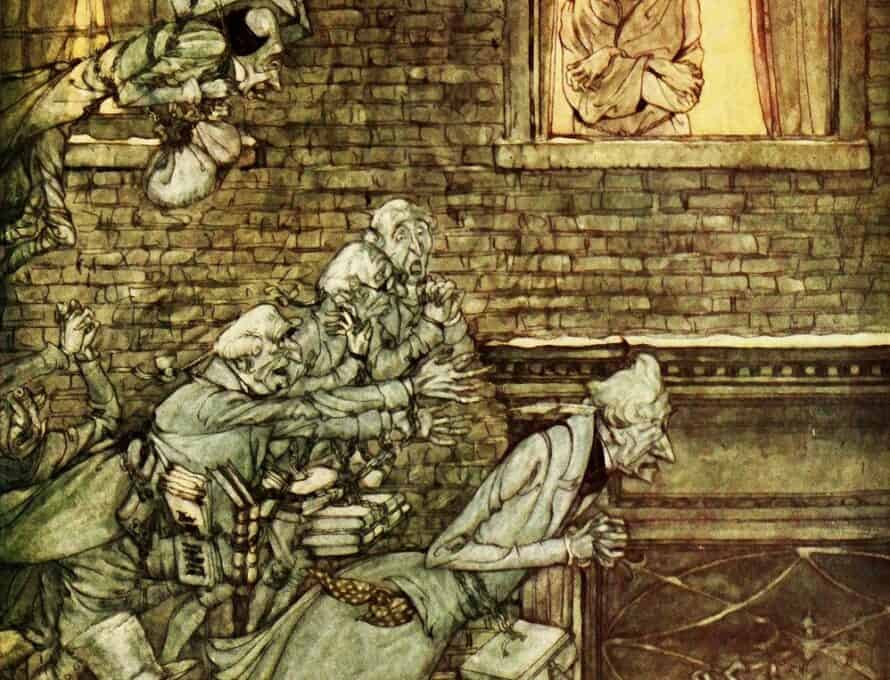

In a monologue that brings to mind Luke 16 and the rich man and Lazarus, the ghostly Marley, literally clad in chains, pleads with Scrooge to learn from Marley’s example and turn from his sins: “I wear the chain I forged in life. I wear it link by link and yard by yard. I girded it on by my own free will, and of my own free will I wore it. Is its pattern strange to you? Or would you know the length of its strong coil yourself?”

As he is visited by three more spirits that night, Scrooge is convicted of the error of his ways. He realizes the irony that though he has gotten rich keeping the debts of others, he can’t repay the debts caused by his sins. When he wakes on Christmas morning and throws open the window, he sees a path forward, a path of joy. The story concludes as he forgives debts, buys enormous turkey dinners for the poor, and offers his beleaguered clerk a raise. He becomes “as good a man as the good old city knew….” and “it was always said of him, that he knew how to keep Christmas well.”

To call Dickens a hero for sneaking a few Christian themes into popular culture is perhaps giving him a bit too much credit. He was not without some faith background; his family were Anglican, and he attended a Baptist church on occasion. I can’t comment on the state of his soul, but judging by his literary works, his faith and morality were more of a social reaction to excesses of the time than a sincere devotion to Christ. G. K. Chesterton wrote that Dickens had “that dislike of defined dogmas, which really means a preference for unexamined dogmas.” Though Scrooge is redeemed in the end, he is redeemed by himself and his devotion to being generous in a humanitarian “spirit of Christmas” sort of way. Talk about an unexamined dogma!

As believers, we know that being generous is laudable, especially at Christmastime, but it is so only because of the context of the true “meaning of Christmas.” Despite what we see on the Hallmark channel, Christmas is about infinitely more than “being with the ones you love” or putting a $5 bill in the Salvation Army kettle: It’s about marking the incomprehensible love of the Heavenly Father who sent His only begotten Son.

That’s not to say we should feel obligated to ignore or dismiss A Christmas Carol. It does tell a very engaging story and does have a sound moral teaching (greed most certainly is a sin). The Spurgeon Center at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary notes that Charles Spurgeon “loved the story.” A nine-year-old boy when the novella was published, he ultimately purchased a copy to include in his personal library alongside his favorite work of fiction, Pilgrim’s Progress.

Christmas was quickly becoming a commercialized event in Dickens’ and Spurgeon’s day. But while Dickens saw Christmas as a way to remind his cosmopolitan culture of the poor, downtrodden and orphaned, Spurgeon saw it “as an opportunity to tell an old story about the ‘the grandest light in history.’” One goal is good, the other goal is infinitely better.

Flawed though A Christmas Carol may be, I think it’s flaws can also be an opportunity to point to that “grandest light in history.” I can see families gathering around a fire to watch/read the story, followed up with a rousing discussion. By contrasting what Dickens meant when he said Scrooge “knew how to keep Christmas well” with a Bible-based examination of redemption and godly living, A Christmas Carol is an excellent segue into the deep truths that are the actual “meaning” of Christmas.

In that respect, this Christmas ghost story isn’t scary at all; it’s one of hope (even if Scrooge’s hope ultimately is incomplete). To quote Spurgeon again, this time is one for Christians to “ring the bells of your hearts, fire the salute of your most joyous songs, ‘Unto us a child is born, and unto us a Son is given.’ Dance, O my heart, and ring out peals of gladness! Ye drops of blood within my veins, dance every one of you! Oh! all my nerves become harp strings, and let gratitude touch you with angelic fingers.”

Now, that’s keeping Christmas well.