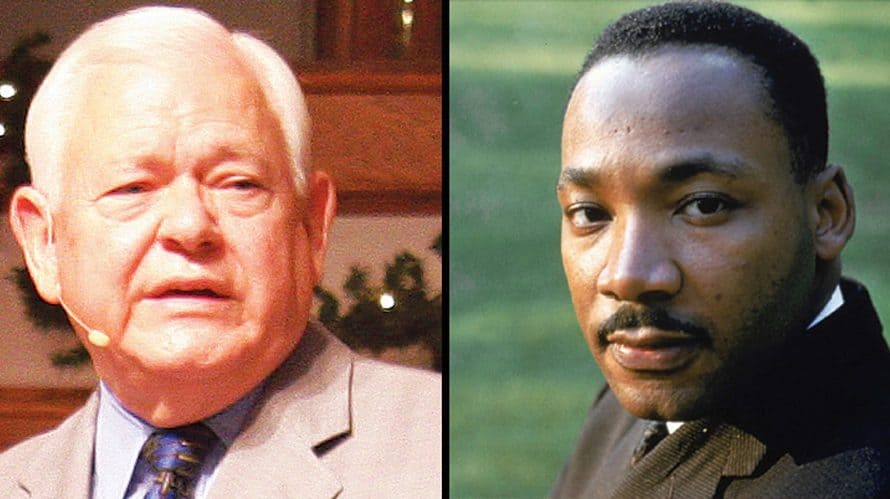

FERGUSON – Stoney Shaw was just an idealistic seminary student, the white son of Florida sharecroppers who grew up alongside the black children whose families worked those same fields. But his experience with racism, protests and a chance encounter with Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1967 would shape him into a man uniquely equipped to pastor a church like First Baptist Church of Ferguson, a town now known internationally – fairly or not – as a hotbed of racial unrest and violence.

“We grew up, black and white together,” Shaw said, “but everything social was separate. One time on the way to church we passed a black church, and I asked my daddy why we didn’t go to that church. He didn’t say anything bad, he simply said that it wasn’t our church. I can’t say it for the whole South, but I was taught to respect everyone, black or white. But there’s no doubt that between a six-year-old black child and a six-year-old white child, the white child had a better shot.”

***

Shaw and his wife, Robbie, began marching for civil rights while in college at Florida State University. They were spurred on after seeing blatant acts of racism and wept as reports of violence around the country filtered in. They were pleased when the church they attended voted to allow church black to join, but ashamed it was only by the slimmest of margins: 615 votes to 612. The next Sunday, the church’s ushers still turned blacks away.

“What a testimony that church could have been!” Shaw said. “But that’s what a lot of churches were doing.”

Shaw got more involved when he went to seminary at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville. There he joined those calling for an equal housing law in the city.

“One night at supper my wife looked at me and said, ‘You’re going to go march, aren’t you?’” Shaw said. “I said, ‘There is probably a black couple on the west end of Louisville that has a two-year-old son, and I think they want the same opportunities to find a place to live that we want for our two-year-old son. I think I have to go.’ It was so clear why I wanted to march with Martin Luther King.”

King’s brother, A.D. King, was pastor of Zion Baptist Church in Louisville at the time and hosted his more famous brother at the church where Shaw heard him preach two sermons, including his famous sermon, “I’ve Been to the Mountain Top.”

“It was so powerful,” he said. “I had cold chills; he was that powerful a communicator.”

Though Shaw could never have the firsthand experiences of discrimination and hate endured by many of those seeking equal rights, he was struck by the reaction of an elderly black woman seated next to him during King’s sermon.

“She was rocking back and forth crying ‘Oh let it be, Lord. Let it be,’” he said. “I feel like that gave me a small bit of insight. I don’t want to get too romantic about it, but it was almost like listening to a prophet of old. If I tried to preach that sermon I’d fall flat on my face.”

***

Just like his wife said he would, Shaw went out and marched for equal housing in Louisville. He marched several times, but one night in particular he and another seminary student – the only two white people there – were marching around City Hall when he rounded a corner and came face to face with the civil rights icon.

“There [Martin Luther King, Jr.] was, leaning up against a wall talking with reporters,” Shaw said. “He was so famous, we couldn’t help but look at him and he was looking at us. So we marched around again and when we came back around he began walking over to us. He stopped us and said ‘Good evening.’”

Shaw and his fellow student stopped and greeted him, then King asked, “Can I ask you boys a question? What are you boys doing here?”

He told King the same thing he had told his wife, that he felt a black boy across town deserved the same access to housing that his white son did.

“He smiled and said, ‘Good answer.’”

There wasn’t time for more of a conversation because King’s cohorts, Jesse Jackson and Ralph Abernathy, came and took him away from Shaw and around the corner. Around the other corner came “storm troopers” and Shaw and the others remaining were arrested.

He would again be arrested for protesting, this time at Churchill Downs, though each time civil rights lawyers stepped in and charges were dropped,.His wife still had bail him out of jail after a few nights.

“I’ll never forget the day of my arraignment,” Shaw said. “My wife was there holding our two-year-old in her arms, along with all the news media, and he reached out and yelled ‘Hey Daddy!’”

Another night when he and a fellow student were arrested for protesting, he signed in at the jail, the front of a long line of protestors. Along with his name, he wrote his address: 2528 Lexington Road, the address of Southern Seminary.

“Unbeknownst to me, all the black students that had bussed in from another college had used our address,” Shaw said. “Duke McCall [the president of the seminary] called me and my buddy into his office and said we made it look like the entire seminary had gotten arrested! I respected him a lot, but I said, ‘Don’t you teach us in ethics class to stand for righteousness? That’s what we did.’ He changed his tune, but said we’d caused him a lot of trouble.”

Though he has more civil rights bona fides than the average Missouri pastor, he points out that the only thing he really feared was “some redneck from Louisville throwing a bottle at my head and causing me to miss a day of seminary. Other people were willing to die.”

***

Fast forward nearly 50 years, and Shaw is the pastor of First Baptist Ferguson. Racially diverse by the standard of most Southern Baptist Churches, roughly 35 percent of the congregation is black (though that figure is still significantly lower than 70 percent black population of Ferguson) and the church’s student minister is black.

Though even now blacks and whites greet each other on Sunday mornings with hugs, the burned out shells of businesses like Walgreens and Little Caesar’s Pizza are mere feet from the church’s parking lot, symbols of sin, tension and anger that dominate TV screens and newspaper headlines. Angry protests and arson erupted in August after a white police officer shot and killed Michael Brown, an unarmed black 18-year-old who he said was attacking him, and then again in November when the grand jury declined to bring charges against the cop.

“I don’t feel guilty about anything that happened; I have done nothing wrong,” Shaw said, “but this did happen on my watch and I must respond. If we’re going to be one as brothers and sisters in Christ, I need to repent of my sins and make sure the beam is out of my eye before I can reconcile with you.”

Shaw and other area clergy – black, white, Hispanic and anyone else who wants to join – are combining later this month to sign the Ferguson Declaration, a statement acknowledging sins of the past and committing toward working toward a reconciled, unified, and forgiving future. Tony Evans, a black pastor from Dallas will speak at the official declaration time Jan. 25-26 in Ferguson. Police, the governor and other leaders have been invited to attend, but not to speak.

“We want people to see that yes, some bad things did happen in Ferguson, but look what God is doing in the aftermath,” Shaw said. “White and black neighbors are talking together and we’re coming closer than we ever have been. Out of the bad, God can do good. If nothing else, the clergy have all gotten together. I have sixty new brothers in Christ.”

Shaw said he senses God is calling him to something else and is nearing the end of his time at Ferguson.

“I’m blessed to be where I’m at and to be here to be part of something bigger than myself,” he said.

***

So much of the violence in Ferguson in the days after the initial shooting and after the grand jury decision was railing against perceived – right or wrong – flaws in the justice system. Looking back, Shaw said what he admired most about King was that the civil rights leader believed in true integration and working through the legal system.

“A lot of radicals have ridden into town on the coattails of Michael Brown,” Shaw says. “There are so many narratives and agendas. I don’t mind saying that Al Sharpton’s narrative is different than ours. I think if they had silently protested, things would have looked much different. King was the other way around. He knew there were some radicals, but he was always preaching nonviolence while there was violence all around him. He would allow himself to be arrested and if he was convicted, he would go back and spend 30 days in that jail. He would say that until we changed the law, he must obey the law. I admired that. He had daily death threats and I thought that if he kept it up someone was going to shoot him, and ultimately they did. He was what he was preaching about and was laying down his life. If people resist observing Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, it shows that they don’t know the true history or who he really was.” ν