SPRINGFIELD – If you have a question about a U.S. president, you might ask John Marshall.

Upon his retirement as long-time pastor of Second Baptist Church, here, he began diving deep into the histories of America’s 46 top executives.

“I set out to read a major biography of every president,” Marshall said. “It took me two years, but I did it: 20,000+ pages. I plowed through them, reading the Pulitzer Prize-winning ones first.”

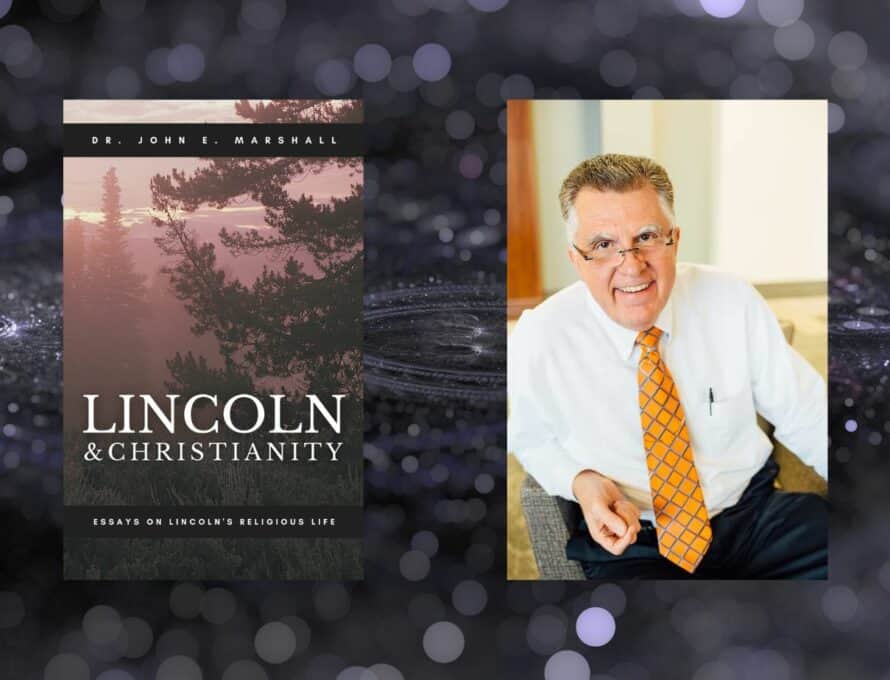

And now, the current interim at National Heights Baptist Church, here, has released his own book of biographical essays, Lincoln and Christianity: Essays on Lincoln’s Religious Life.

But the roots of those essays began even before Marshall began getting deep into the lives of the presidents. In the early 2000s, Hollywood titan Steven Spielberg announced he was producing a movie on the 16th president. That movie languished in limbo for a while, before eventually releasing as 2012’s “Lincoln,” starring Daniel Day Lewis. Already a fan of presidential biographies and of Lincoln’s story in particular, Marshall saw the increased interest and began writing essays on Lincoln and his connections to Christianity. Those essays eventually evolved into the book.

“Of course, I love Lincoln,” he said. “Everybody loves Lincoln. We respect the emancipation of the slaves and his bulldog determination to fight the Civil War, even with his cabinet and other leaders against him. There’s no one like him in that he made massive decisions standing alone. Washington was close, but he had the advantage of knowing he was invincible and could do anything. Lincoln planted his feet and made decisions without that protection. I’ve always had that appreciation for him, but after reading all the biographies, I was convinced I was right.”

Though Lincoln never made a public profession of his faith, there is zero doubt Christianity and the Bible played a pivotal role in his live, and that’s what Marshall’s essays explore: Lincoln and thanksgiving, his connection to Baptists, his frequent interactions with Scripture, his relationships with clergy, and ultimately the underpinnings of his opposition to slavery.

“Lincoln grew up a Baptist,” he said. “Hard-shell Baptist, almost, and that upbringing is why he was strongly, radically anti-slavery. They were dyed-in-the-wool Baptists, though Abraham never joined the church. He struggled his whole life with how to know if you’re a believer. He did not become an atheist, he came close and was right up against the edge.”

Lincoln lost his sons and, of course, was faced with grave challenges during the darkest days of the Civil War. But that, Marshall said, is when Lincoln shined.

“From then to end is when he wrote the Gettysburg Address and the second inaugural – which is the greatest sermon ever preached in American history, probably – and you could see him moving away from his position of being frozen against God. How far did he come back? We don’t know. He never made a profession of faith, and he never claimed to have a relationship with the Lord.”

So even if his life isn’t a testimony to the Lord – indeed, Marshall points out that not a single pastor in his hometown voted for him, probably due to not being a professing believer – he is still a testimony to common grace and the influence of Scripture and Christianity in the public square.

For example, Lincoln’s second inaugural address – the one Marshall calls possibly the greatest (or at least most famous) American sermon ever preached – is an application of four verses. In 703 words, he mentioned God 14 times, expounded on Genesis 3:19, Matthew 7:1, Matthew 18:7 and Psalm 19:9, and spoke of prayer three times. Before Lincoln, a reference to God was relegated to the final paragraphs of inaugural speeches, and only once had the Bible been quoted, by John Quincy Adams. (In more recent days, both Joe Biden and Donald Trump referenced God three times, with no Scripture references in their inauguration speeches.)

Lincoln and Christianity: Essays on Lincoln’s Religious Life is available as an e-book on Amazon.com, and Marshall said he is exploring the possibilities of a printed version.