LONDON, England – In 1612, eight years before the Pilgrims set sail for the New World to find a home where they could worship together in freedom, English Baptist pastor Thomas Helwys proclaimed a message that would transform Western civilization for centuries to come.

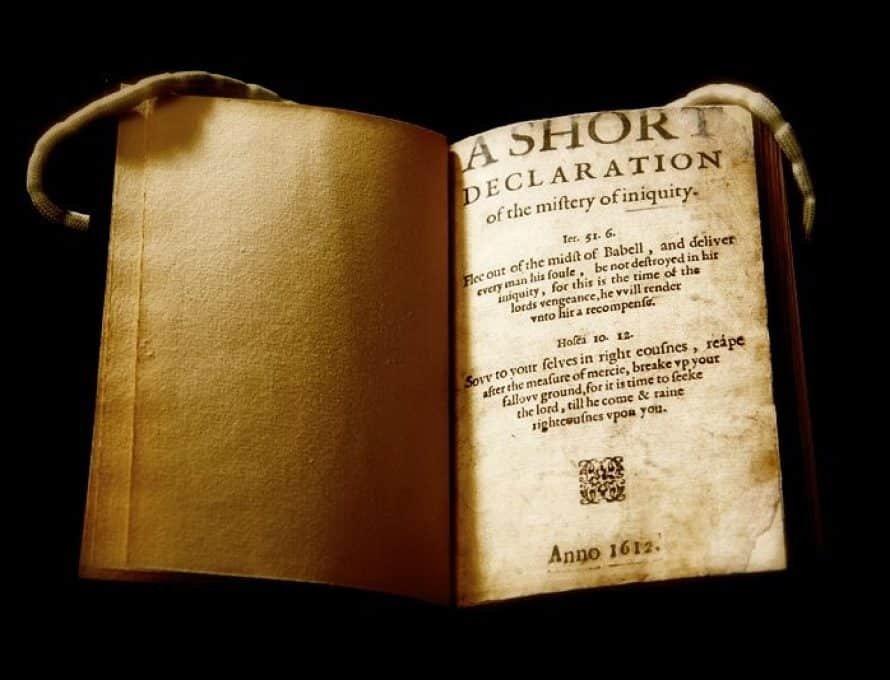

Writing to King James I, Helwys published a tract called A Short Declaration of the Mistery of Iniquity, and in it he wrote the following inscription: “Hear, O king, and despise not the counsel of the poor, and let their complaints come before thee. The king is a mortal man and not God, therefore has no power over the immortal souls of his subjects, to make laws and ordinances for them, and to set spiritual lords over them. If the king has authority to make spiritual lords and laws, then he is an immortal God and not a mortal man.”

He added, “Men’s religion to God is between God and themselves. The king shall not answer for it. Neither may the King be judge between God and man. Let them be heretic, Turks, Jews, or whatsoever, it appertains not to the earthly power to punish them in the least measure.”

The year before he published these words, Helwys returned to England from the Netherlands with his congregation. They were the first Baptist church ever planted on English soil. Despite the persecution they would face, they desired to bring the light of God’s word back to their homeland.

Unknown to many people today, this same group of Baptists had a direct connection to the Pilgrims who later sought freedom on the shores of Massachusetts.

The journey of the Baptist congregation began, in 1608, when Helwys and his followers fled persecution as part of a separatist congregation led by John Smyth. This was the second separatist group from England to settle in Amsterdam, and for a short time Smyth’s congregation dwelt peacefully alongside the congregation led by Francis Johnson. But in time a dispute broke out between the two churches about the biblical definition of church leadership.

This dispute exacerbated tensions within Smyth’s own congregation. And, about 100 members led by John Robinson split from the church and moved to the city of Leiden. Eventually, Robinson’s congregation set out from Plymouth, England, to the New World. These Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock in 1620.

Meanwhile, Smyth became convinced that infants are incapable of faith or repentance and, therefore, that they shouldn’t be baptized. In 1609, he instituted believer’s baptism within his church by baptizing himself and then the members of his congregation. In doing so, he established the first ever English Baptist church.

But Smyth’s spiritual journey continued. Concerned that his self-baptism was inappropriate, Smyth joined the Dutch Waterlander Mennonites. The Englishmen and women who followed Smyth settled into an Amsterdam Bakehouse purchased from the Mennonites and eventually were integrated into Dutch society.

But part of Smyth’s congregation, led by Helwys, returned to England to proclaim God’s word. This church of “General Baptists”—so called because they believed in general atonement, in contrast to the Reformed doctrine of particular atonement—called the king to tolerate the various religious groups in England.

Established a few decades later, England’s “Particular Baptist” churches—which were basically Reformed in their beliefs— likewise defended religious liberty. As stated in the 1689 London Baptist Confession of Faith, “God alone is Lord of the conscience, and hath left it free from the doctrines and commandments of men which are in anything contrary to his word, or not contained in it.”

Likewise, Baptists in the American colonies would carry on the tradition of defending religious liberty, becoming key proponents of this freedom as the Bill of Rights was drafted and approved by the fledgling United States of America. In 1773, Isaac Backus wrote, “Religious matters are to be separated from the jurisdiction of the state, not because they are beneath the interests of the state but, quite to the contrary, because they are too high and holy and thus are beyond the competence of the state.”

Similarly, in 1791, John Leland declared, “Every man must give an account of himself to God, and therefore every man ought to be at liberty to serve God in that way that he can best reconcile it to his conscience. If government can answer for individuals at the day of judgment, let men be controlled by it in religious matters; otherwise let men be free.”