KEARNEY – Poring over microfiche of Kearney’s First Baptist Church business meeting minutes, one finds the November, 1867 membership list. At the top of the page, in the left-hand column in tight, careful script, lies probably the most famous – or, more rightly, infamous – name in Missouri Baptist history: Jesse James.

As one might imagine, the role that an outlaw plays in First Baptist Church’s past is met with mixed emotions.

“Some don’t want to admit he was ever a part of the church,” said Ken Parker, pastor of present-day First Baptist. He said he occasionally gets introduced as “Jesse James’s pastor,” a memorable (if inaccurate) title. “Others recognize it’s a part of history; our history, good and bad.”

See related story: ‘Baptists did not weep at his funeral’

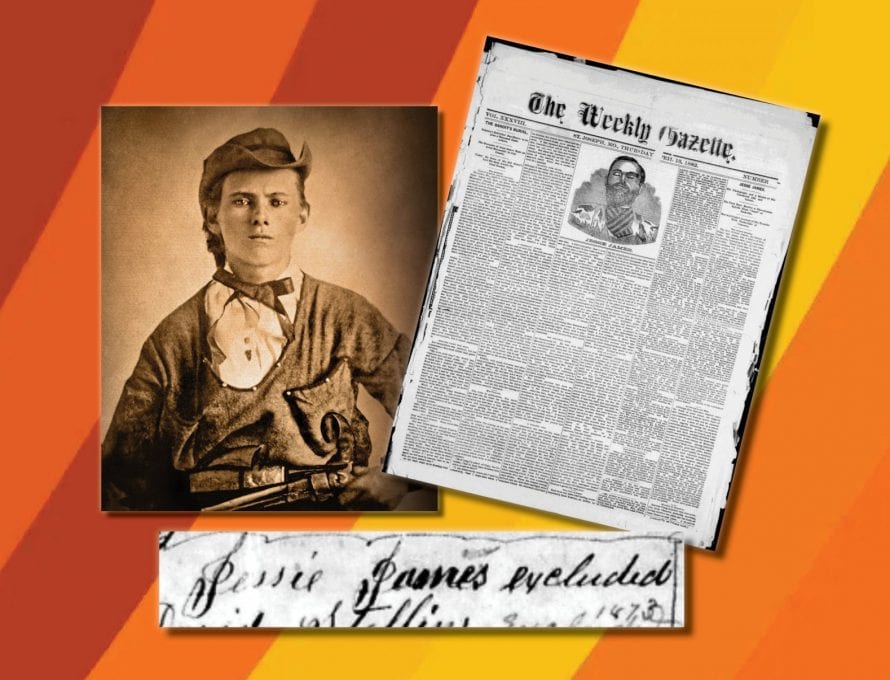

The name Jesse James stirs up a blur of fact and fiction: exciting snapshots of shootouts on horseback. Daring train robberies. Popular legend. The reader can find any number of dime novels or movies to get the dramatic details of his exploits, but the short summary is at least 20 banks, stagecoaches and trains robbed; 17 men murdered – and that’s just what he admitted to. But regardless of how history regards his deeds, the word after James’s name in First Baptist’s membership roll – added years later in different penmanship – hints at the notorious future to come: “excluded.”

Son of a Preacher Man

There’s an old trope that PKs – preacher’s kids – are wild and ill-behaved children. The stereotype might have begun with young Jesse.

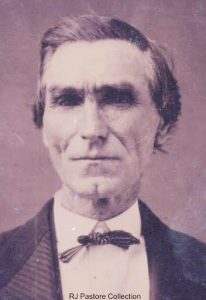

Robert Sallee James

He was the second son born to Zerelda and Robert Sallee James. A Kentucky boy, Robert followed his new bride to Clay County, Mo., in the early 1840s, ready to start his life, family and ministry. There, he became pastor of New Hope Baptist Church (now known as New Direction Church), in Holt in 1843. “… [H]is labors were much blessed, so that in the year following the church numbered 94 members,” writes R.S. Duncan in A History of Baptists in Missouri. The church was noted at the time for “resisting the encroachments of the anti-mission element,” the isolationist and inwardly focused tendency that caused many Baptist churches in the young state to close their doors.

In 1882, a friend of the James family, Frank Triplett, wrote in one of the first Jesse James biographies that Robert was known as “a sincere Christian” and a “cultivated scholar.” Perhaps that is what led him to be one of the founding trustees of what became William Jewell College in Liberty in 1848. (The college would have Baptist ties until the relationship between the school and the Missouri Baptist Convention was severed in 2003). In 1849, he organized Pisgah Baptist Church in Excelsior Springs.

Robert might have continued circuit riding and planting churches if it weren’t for a major event that sent shockwaves through the frontier in 1849: the gold rush. The promise of wealth out West lured many men away from their homes and families in the middle of the 19th century. Histories are contradictory on why Robert headed west: some say it was to seek his own fortune, some say he was escaping his marriage, while others say it was to shepherd his flock, which had largely picked up and followed the gold rush themselves. Either way, he bid farewell to his wife and two sons – seven-year-old Frank and two-year-old Jesse, reportedly expressing his intent to return. Jesse, it was said, grasped onto his father’s knees and bawled as he begged Robert not to leave. But Robert did leave, and the preacher-turned-gold-hunter died unexpectedly of suspected cholera just a few months after he left in 1850.

Zerelda would remarry, twice. She and the boys soon began attending Mount Olive Baptist Church in Centerville (Centerville would later be renamed, Kearney, and Mount Olive became known as First Baptist in 1872).

War and (No) Peace

Robertus Love, in The Rise and Fall of Jesse James, wrote that both the James boys were “schooled deeply in the old-fashioned religion.” Every Sunday, the family drove to church in the wagon. Love also reports that “Jesse James believed in a personal God and in a personal Devil – probably in a considerable number of the latter! … He expected to go to Heaven when he died, for he believed that he had lived the best life he possibly could live under all the circumstances, and that, therefore, he was entitled to salvation.” Flawed theology aside, the records of First Baptist do show he was at one time a member in good standing, joining by baptism. But if his conversion and faith were genuine then, the fruit was far from obvious in the coming months and years.

The James family was not at peace. Neither was the rest of Missouri. Jesse and Frank both fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War. Though they were just teenagers, both were members of Quantrill’s Raiders, guerilla warriors that fought in some of the bloodiest skirmishes against the “Jayhawkers” along the Missouri-Kansas border. When the war was over, factions split Missourians’ loyalties and Reconstruction wreaked havoc on the state’s social and economic structures. The James boys were not alone in lashing out at what they saw as the Union forces stomping on the already-defeated South. Regardless of their politics, Jesse and Frank were not going to live quietly after the war.

KEARNEY – Jesse James’s name as it appears (mispelled) in the November, 1867 list of Mount Olive Baptist Church in Centerville, now known as First Baptist, Kearney. The “excluded” was added two years later, apparently at his request.

‘Excluded’

At just 18 years old, Jesse James robbed the Clay County Savings in Liberty in 1866, a few months after the Civil War came to an end and a year before his name was added to the church roster. It was the first of many robberies to come. It’s not clear if the James boys would listen intently to fire and brimstone on Sunday – shouting, “Amen!” – and then go out and rob a train on Monday, shouting, “Reach for the sky!” But tradition does say an adult Jesse sang in the choir, and some say Frank taught Sunday School.

By the fall of 1869, Jesse’s name would be taken off the rolls at Mount Olive. Curiously, it was Jesse himself that initiated the process. The business meeting minutes from September-October, 1869, say the church voted to send two men to “visit Bro. Jessy [sic] James and ascertain his reasons for wishing his name withdrawn from our church book.” The two-man committee set out with instructions to report back at the next business meeting. When the next session rolled around, the first order of business was a vote to exclude James from the church. The motion carried.

“It does leave us with some interesting questions,” Parker said. “Did he know his lifestyle was inconsistent with biblical values? Did he wish to somehow distance the church from his own misdeeds? Did he think he was beyond the realm of experiencing God’s forgiveness? It’s certainly a weighty matter, but to their credit, it seems the church did the proper thing. Who knows exactly how much backlash removing Jesse James from the membership roll might have caused them? Who knows whether or not their exclusion of him caused him to contemplate the experience of personal salvation he had at one time expressed?”

Though this is the final mention of his name in First Baptist’s official records, Jesse’s final dealing with the church wouldn’t come until 13 years later.

Live by the Six-Shooter, Die by the Six-Shooter

Jesse and Frank made quite a reputation for themselves over the next few years. Jesse married and they had two children, but he hardly “settled down.” The James brothers and their gangs robbed banks, held up stagecoaches and busted fellow outlaws out of jail from Mississippi to Kansas, from Minnesota to Texas. They killed at least two dozen men between them, including lawmen tasked with bringing them to justice. They claimed they stole only from the rich. This helped lend them a bit of a gun-slingin’ Robin Hood flair, but the losses from banks they robbed in Missouri almost certainly impacted the people with whom they once worshipped.

They and the James-Younger gang ricocheted across the South and Midwest in a 15-year cloud of dust and gunfire. After a string of robberies in Louisiana, Jesse escaped to St. Joseph in 1881 to lay low. Ted Yeatman writes in Frank and Jesse James: The Story Behind the Legend, that the two outlaws were ready to “retire and give up their lives of crime.” They’d stolen more than $200,000 during their “careers,” equivalent to more than $3 million today.

With most of his former gang dead, incarcerated or dispersed, Jesse was a little paranoid alone at home. He asked the Ford brothers – Charley and Robert – to move in to protect him and his family while he began planning – what else? – more robberies. However, Robert had been secretly communicating with Missouri Governor Thomas Crittendon and made plans to betray James in exchange for a $5,000 reward.

By Robert Ford’s account, after breakfast on April 3, 1882, the Fords and James went into the living room before traveling to Platte City for yet another bank robbery. Robert said in newspapers at the time he believed James suspected the Fords were going to betray him. Rather than confront them, Robert said James walked calmly across the living room and laid his Smith & Wesson .45 revolvers on a sofa. He noticed a dusty picture above the mantlepiece, and climbed onto a chair to clean it. Robert drew and shot Jesse in the back of the head.

‘Few of Days and Full of Trouble’

The front page of April 13 edition of the St. Joseph Weekly Gazette, devoted its entire front page to coverage of Jesse James’s death and funeral.

Even if people disagreed during his lifetime on whether James was a hero, a terrorist, or something in between, his death was a landmark event. The St. Joseph Weekly Gazette gave its entire front page on April 13, 1882 to the news and coverage of the bandit’s burial.

First Baptist, St. Joseph, refused to host the funeral, but J.M.P. Martin, pastor of what was by then First Baptist, Kearney, officiated a service at Jesse’s mother’s request. The newspaper reported that more than 350 packed the church. Martin read from Job 14: “Man that is born of a woman is of few days and full of trouble.” He called on those present to repent, and they sang “What a Friend I Have in Jesus.”

“[Martin’s] delivery of the grand passages was striking,” the Weekly Gazette reporter wrote, “and his subsequent prayer an impressive calling upon the Almighty for strength to the bereaved – but he didn’t say anything about Jesse James.… If there were within those four crowded walls any who had looked for this address with eager curiosity, their disappointment was complete. Not an allusion was made to the man in the coffin.”

Theories swirled that Jesse James escaped Ford’s attack. The body was exhumed in 1995, and DNA tests proved that it really is Jesse James’s body that lies in First Baptist’s cemetery to this day. Parker said tour buses of curiosity-seekers still stop at the cemetery, though many of them leave underwhelmed: “His grave is like most of the others from that era and there’s certainly no shrine to the man or his deeds,” he said.

‘God’s Grace is Greater’

Though his flock’s most well-known member is a black sheep, Parker said the church’s history is worth remembering. And though one man didn’t live up to the truth of the gospel, it doesn’t change the church’s gospel mission.

“To think someone could sit under gospel preaching week in and week out and end up squandering his life as he did is tragic, but there’s no need to ignore history,” Parker said. “Any of us could have been Jesse James, and God’s grace is greater than Jesse James’s sin, or your sin, or my sin. That gospel truth is exactly what we’ve been doing since Christmas Day of 1856 when our church assembled for the very first time.”