WARRENSBURG – When Matthew Argotsinger and Cameron Rogers started college at University of Central Missouri (UCM) two years ago, neither of them foresaw using their degree in Design & Drafting Technology (CADD) to provide comfort for frontline pandemic healthcare workers. But in a world drastically altered in a matter of weeks by the novel coronavirus, that’s exactly what they’re doing.

Both Argotsinger and Rogers, student leaders with the BSU at UCM, discovered their passion for the diverse field of CADD while in high school. “You’re designing everything from a box of cereal to a nuclear plant,” says Rogers. For Argotsinger, watching his father’s experience in the construction industry made him excited to help bridge the gap between the highly technical work of engineers and the pragmatic work of the construction force. “We’re like the missing link,” he says of CADD.

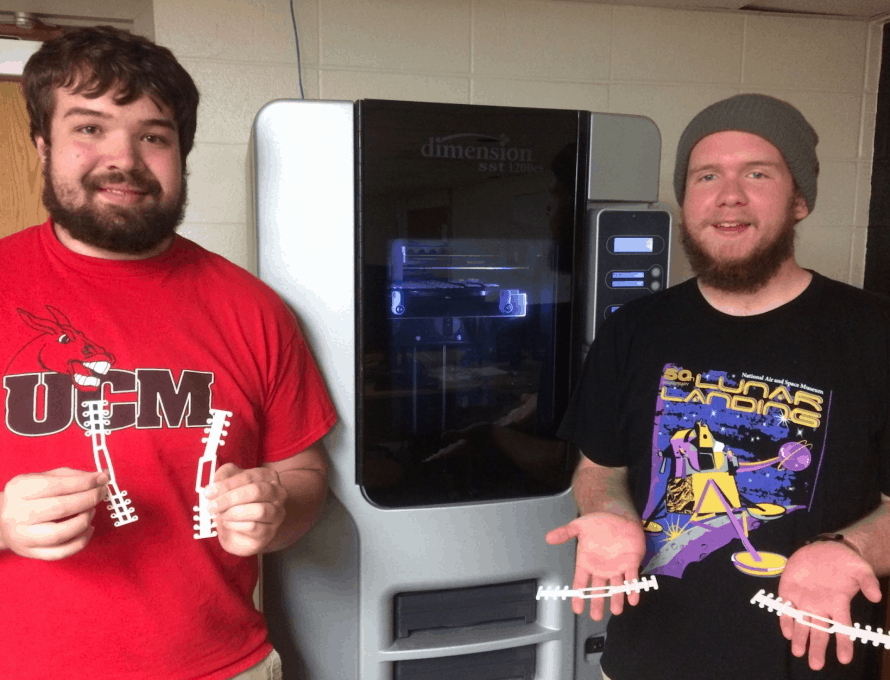

When the coronavirus hit, Argotsinger read about people using 3D printing devices to produce ventilators and other lifesaving components. He started to wonder what he could make that would be helpful in Missouri, where “we’re not in a huge crisis where we need the critical lifesaving components right now,” he says.

A Facebook post by a young boy from Canada provided the inspiration he needed. The youth had freely shared his design for an ear guard that changes the way protective masks are worn. Instead of looping over the backs of the ears, the mask hooks onto the guard at the back of the head. With healthcare workers’ ears rubbed raw from wearing uncomfortable masks for hours on end, Argotsinger knew ear guards could be a gamechanger.

Rogers heard what his friend was doing and immediately wanted to team up. “Out of everything we could have printed to add to this cause, ear guards are the fastest and cheapest thing to produce,” he says. “They may not help fight COVID-19, but they definitely help the people on the frontlines who are fighting against it.”

UCM agreed to fund production using the school’s resources that are currently sitting idle with classes moved online. They began printing on April 5th “without any clients,” Rogers says. When they contacted Western Missouri Medical, they were blown away by the hospital’s request for at least 400 ear guards.

Within the first week, they had met and surpassed that goal, working long hours every day, adjusting the printer specs to perfection, and dealing with a long power outage that brought production to a halt. “3D printing isn’t the most efficient,” Argotsinger says. “It’s meant for prototype, but in this pandemic with shortages, it’s been really useful.”

“They were incredibly grateful,” Rogers says of Western Medical’s response to the ear guards. Now that they have surpassed the hospital’s minimum request, they may continue printing for more for Western or other local facilities. Even if material shortages and funding don’t allow that, they hope to “inspire other people or schools to start doing the same.”

That hope is already coming to fruition. In just a matter of days, they received inquiries from people at Cox Hospital in Branson and all the way from Maryland about how to print the ear guards. In Warrensburg, a man with six 3D printers offered to help. After an article was published on UCM’s website, Governor Mike Parsons applauded their efforts on social media.

For Rogers and Arbotsinger, creating these ear guards is a beautiful intersection of their faith and their career. “I’ve struggled with thinking our major doesn’t impact the church,” Arbotsinger says, “so how can I be useful in the church?” He’s realizing that “everyone has their purpose.” Similarly, Rogers is “starting to see that serving the community and serving those who serve God is a calling, too.” Their BSU campus missionary, Atticus Dyer, has instilled in them the mindset that wherever they go and whatever they do, there are people who don’t know Christ and opportunities to share the gospel.

For now, that means using their education and talents to create and distribute ear guards and inspire others to do the same. “If we get to talk to people and it leads to building relationships, maybe we’ll get to share the gospel,” Arbotsinger says.

“Some designers go to Africa and design layouts for water pumps and stuff,” says Rogers. “We can’t do that here, but this is a way to serve our community.”