EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the latest article in a year-long series, commemorating the history of the Conservative Resurgence of the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) in honor of its 40th anniversary. To read previous articles, visit www.mbcpathway.com/ConservativeResurgence.

DALLAS (BP) – For pastor’s wife Ritchie Hale, attending the 1985 Southern Baptist Convention annual meeting meant sleeping in a 1960 popup camper with her husband and four children amid 100-degree temperatures and thunderstorms. For Conservative Resurgence leader Morris Chapman, that meeting occasioned one of the clearest personal directives God had ever given him. For moderate leader Cecil Sherman, it was the first time he contemplated losing the battle for the SBC.

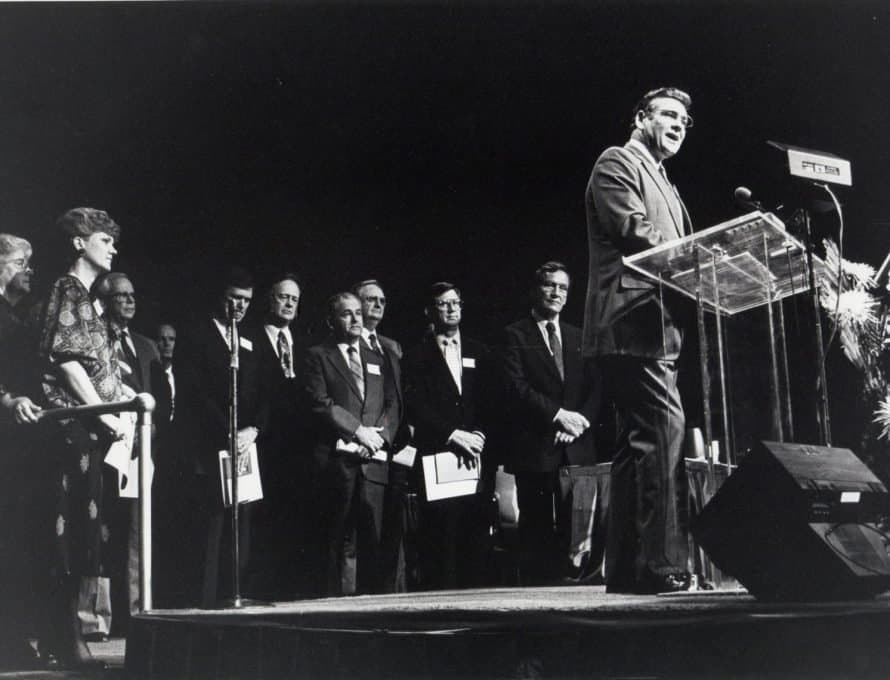

All three knew the 1985 Dallas annual meeting was of monumental importance in the SBC’s Conservative Resurgence. By some estimates, the 45,519 registered messengers may have constituted the largest deliberative body ever assembled.

“The 1985 annual meeting was a watershed moment in the conservative revolution in the convention,” said Gregory Wills, research professor of church history and Baptist heritage at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary. “Southern Baptist moderates mobilized all their resources to stop the conservative advance at the Dallas meeting. Their bid to regain the presidency failed.

“Equally important was the convention’s vote to appoint what became known as the Peace Committee, whose work affirmed that the controversy in the SBC derived largely from genuine theological differences,” Wills told Baptist Press in written comments.

A turning point in the resurgence

Hale, whose husband Sheldon pastored Liberty Baptist Church in Auburn, Ky., at the time, was willing to endure the steamy popup camper parked some 30 miles from the convention center, and dressing four children in their Sunday clothes in campground bathhouses, because she believed reelecting the conservative Charles Stanley as SBC president could make an eternal difference.

Hale’s husband was a student at Southern Seminary, and she found it “disheartening” to hear his reports of professors’ claiming there were errors in the Bible. By electing an unbroken succession of SBC presidents committed to biblical inerrancy, Hale believed messengers could set in motion a process that eventually would return SBC seminaries to their biblical roots.

Chapman’s role in reelecting Stanley, pastor of First Baptist Church in Atlanta, began a few weeks earlier at a McDonald’s in Wichita Falls, Texas, where Chapman was pastor of First Baptist Church. As he ate lunch, “it was as if the Lord said audibly, ‘You are going to nominate Charles Stanley for his second term as SBC president,'” Chapman told BP. He resisted the idea initially because it seemed strange to call a preacher of Stanley’s stature and announce such a clear sense of direction from God.

But that afternoon, Stanley’s associate Fred Powell – a former pastor of Pisgah Baptist Church, Excelsior Springs, Mo., who died in 2017 – called with a message: Stanley wanted Chapman to nominate him. “I [was] really spooked that God was so faithful to make His will for me known so dramatically and clearly,” Chapman said.

When Chapman made his nomination on the convention’s opening day, Stanley was reelected over moderate challenger Winfred Moore by a 55.3-44.7 margin – a victory some attributed to a telegraph from evangelist Billy Graham supporting Stanley that was publicized the morning of the election.

Sherman, then-pastor of Broadway Baptist Church in Fort Worth, Texas, had campaigned against Stanley in the months leading up to the Dallas meeting. Sherman believed SBC conservatives’ attempt to limit positions of denominational service to proponents of biblical inerrancy would damage the convention’s historic cooperation for missions and evangelism. Along with fellow moderate Larry McSwain of Southern Seminary, Sherman believed 16,000 votes for Moore would defeat Stanley and stem the tide of the Conservative Resurgence.

Counting on at least that many moderate votes, Sherman “went to Dallas with hope that we would elect a president,” he wrote in his 2008 memoir “By My Own Reckoning.” When Stanley was elected despite 19,795 votes for Moore, Sherman, who died in 2010, had a realization: “It was in Dallas that I first allowed myself to think of losing the SBC to political Fundamentalism,” Sherman’s label for the SBC’s conservative movement.

“A lot of strollers”

The 45,000 messengers, plus guests, denominational employees and members of the media, who descended on the Dallas Convention Center caused a host of logistical problems. Two overflow halls had to be opened because the main hall seated only 31,000 – a capacity nearly four times greater than the chairs set up for this year’s SBC annual meeting in Birmginham, Ala.. Restroom lines were so long that “desperate women and children finally began commandeering the relatively less-used men’s rooms,” according to sociologist Nancy Ammerman in her book, Baptist Battles.

Hale remembers “a lot of strollers” and “lots of moms walking the back with babies on hip.” Young families – “scads” of whom came on “shoestring” budgets – “were there in mass because they really believed in being a part of the decision-making process.”

The Hales remained in their seats each day of the meeting, including lunchtime when they ate picnic meals. The children – ages 13, 11, 11 and 6 – were required to listen to one sermon per session and participate in the music. But during the consideration of business, they could entertain themselves with craft bags their mother had prepared.

Among the more creative crafts they fashioned was a set of pipe cleaner glasses modelled after Stanley’s. The three-day meeting afforded them ample time to hone their ability to mimic Stanley’s method of adjusting his glasses.

For Chapman, chair of the meeting’s Committee on Order of Business, meal breaks meant work – especially related to a controversial motion made by moderate James Slatton of Virginia.

When the Committee on Committees proposed its nominees to the Committee on Boards (now called the Committee on Nominations), Slatton attempted to amend the committee’s report by substituting each state convention president and each state Woman’s Missionary Union president for the committee’s slate of nominees. If adopted, Slatton’s motion could have thwarted the conservatives’ strategy to gain control of the convention by controlling the Committee on Boards.

Initially, Stanley ruled that Slatton’s substitute nominations had to be made on a state-by-state basis rather than all at once, but messengers voted to overturn his ruling. Then during a break, Stanley consulted with parliamentarians as well as the Committee on Order of Business and decided to rule Slatton’s motion out of order – a move that sparked considerable controversy, including a lawsuit against Stanley that eventually was dismissed.

Finally, messengers adopted the original slate of nominees to the Committee on Boards. Ammerman called debate over the Committee on Committees report “as near chaos as I have ever seen at a Southern Baptist Convention.” The debate contributed to the convention’s decision to hire a professional parliamentarian beginning in 1986.

After a session, “Charles expressed some concern as to whether he had ruled correctly on the Committee on Committees discussion in spite of the restlessness of a number of messengers,” Chapman recounted. “The motions and discussions led to a complexity of procedures, but at the end of the day, a number of the people on the platform commended Dr. Stanley for doing a great job in a difficult setting.”

“Point of no return”

One hopeful action of the convention for Sherman and fellow moderates was the election of what became known as the Peace Committee, which would “seek to determine the sources of the controversies in our convention, and make findings and recommendations regarding these controversies.” Sherman was among the committee’s original 22 members, balanced between conservatives and moderates.

The Peace Committee reported in 1987 that theological differences were the primary cause of the SBC controversy. In particular, “the authority of the Word of God is the focus of differences,” according to the committee’s final report.

Sherman eventually resigned from the Peace Committee in frustration, coming to believe the direction of the SBC was set.

“Most Southern Baptists thought the Peace Committee was working toward reconciliation,” Sherman wrote. “In fact, we were buying time for the Fundamentalist takeover to get past a point of no return.”

Though the Dallas meeting had ended, the Hale family was not finished with contentious votes. Using leftover ballots they had collected in the meeting hall, the children voted all the way home to Kentucky on where to take rest stops.