When it comes to fiction, few authors can stir Christians’ (and non-Christians’) imagination like J.R.R. Tolkien. His Lord of the Rings (LOTR) books are rightfully 20th-century classics. While there is zero doubt Tolkien’s deep faith influenced his work – you can’t ignore the themes of temptation, sin, redemption and sacrifice in LOTR – I’ve always appreciated that his writings were substantially subtler than that of his contemporary and friend, C.S. Lewis. Where Lewis’s symbols were resting on the surface of his allegories, Tolkien’s were deeper and more complex. While these themes are not as deeply embedded in the movies of the early 2000s as they are in the books, they are still impossible to ignore.

So it would seem to me that any attempt to tell Tolkien’s own biographical story would absolutely require a look at how his faith affected his writing. Sadly, “Tolkien” (in theaters now), does not even pretend to scratch the surface in that department.

Instead, the movie chooses to focus on school friendships and his experiences in the horrific trench battles of World War One. In his feverish attempts to find one of his comrades, we see dream-like intrusions of LOTR characters on the actual battlefield in 1916 France (dragons, the Balrog, the Nazgul, and even a ball of flame that was intended to be the Eye of Sauron). As he stumbles through the nightmarish hellscape that was the Battle of the Somme, it is a faithful friend named Sam who guides him and pushes him on while all hope seems lost.

No one would argue that World War One wasn’t a very influential time for Tolkien. Book Two of LOTR, The Twin Towers, in particular, speaks about industrialized warfare and the destructive power it has over the innocence of nature. That formational experience no doubt deserves to be included in recounting of Tolkien’s personal story. But, it’s still not the complete story.

“The Lord of the Rings is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision,” Tolkien once wrote in a letter. “We have come from God and inevitably the myths woven by us, though they contain error, will also reflect a splintered fragment of the true light, the eternal truth that is with God. Indeed, only by myth-making, only by becoming a ‘sub-creator’ and inventing stories, can Man ascribe to the state of perfection that he knew before the fall.”

It’s difficult to see the absence of any mention of his religious influences as anything but a whitewashing. It’s also curious for the movie to focus on the early “fellowship” of schoolboys (yes, the movie intentionally used that word) but not on his later time as a member of the Inklings, which included Lewis and other literary luminaries. It was at these weekly teas that Lewis persuaded Tolkien that his stories were more than mere scribblings, and were worthy of publication. It’s also where Tolkien convinced the agnostic Lewis of the truth of Christianity… isn’t that a story you’d like to see?

In April, Tolkien’s family issued a statement saying they weren’t exactly thrilled with the movie, even though they hadn’t yet seen it. “The family and the Estate wish to make clear that they did not approve of, authorize or participate in the making of this film,” the statement said. “They do not endorse it or its content in any way.” This is not particularly uncommon when it comes to biopics, and it should be noted they objected to Peter Jackson’s LOTR and ‘Hobbit’ trilogies. But here, I think they were wise and correct to distance themselves from it even if I have no way of knowing what they’d think of the lack of religious influences.

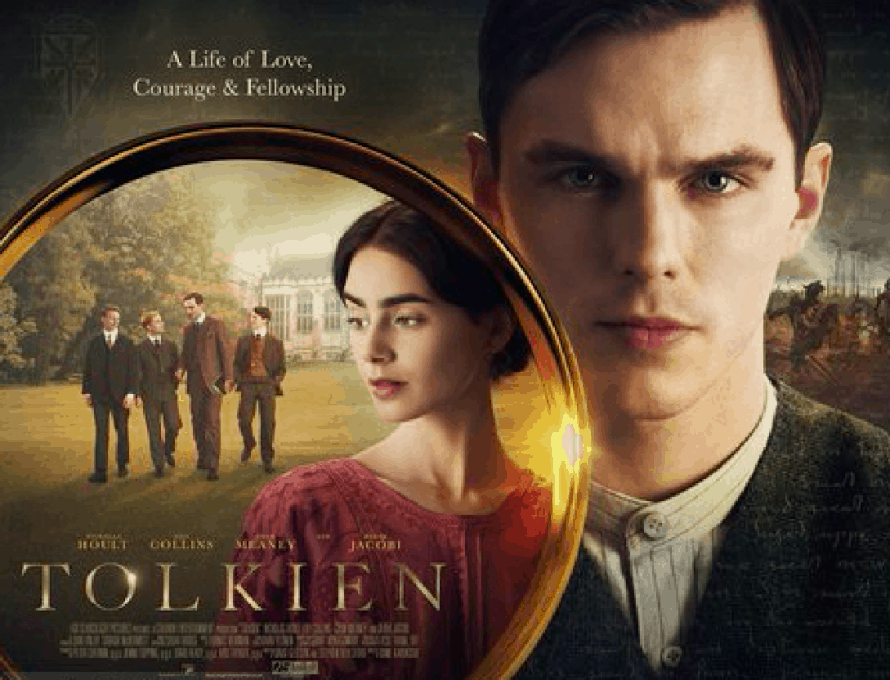

There are some genuinely good moments in the movie, however. When we get to see the young schoolmates being chummy, it’s exactly how you’d imagine creative geniuses would behave while sipping tea and scheming how they will change the world with their art. Nicholas Hoult does a good job playing our hero, while Lily Collins does her best to elevate the thinly written part of Edith, the woman who eventually would be Tolkien’s wife. I enjoyed watching how Tolkien – a master of languages who created a real and usable grammar and vocabulary for his characters – acquired his love of words.

We also get winks and nods to Tolkien’s future classics that will either make the viewer cringe or faintly smile in recognition. For example, when Tolkien and Edith attend a long performance of Wagner Ring Cycle opera, a friend quips, “It shouldn’t take six hours to tell a story about a magic ring.” I was more in the “cringe” category.

You’d do better to spend six hours watching a story about a magic ring.

“Tolkien” is rated PG-13 for its depiction of violence in World War One. Coarse language is all but non-existent. One of Tolkien’s friends is implied to be gay and in love with him, though everything I’ve read says this is completely fabricated.