EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the second article in a year-long tribute, honoring the 40th anniversary of the Conservative Resurgence of the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC). See the previous story, ‘Battle for the Bible’ – 1979 SBC presidential election ignites Conservative Resurgence.

Printed on June 1, 1882, in crabbed typeface at the bottom of the fourth page of the Kentucky Baptist newspaper, The Western Recorder, an editorial notice testifies ultimately to the loss of love and faith:

“The distinguished Oriental scholar, Prof. C. H. Toy, formerly of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary,” the notice reads, “is shortly to be married to a young lady who has been a missionary to China.”

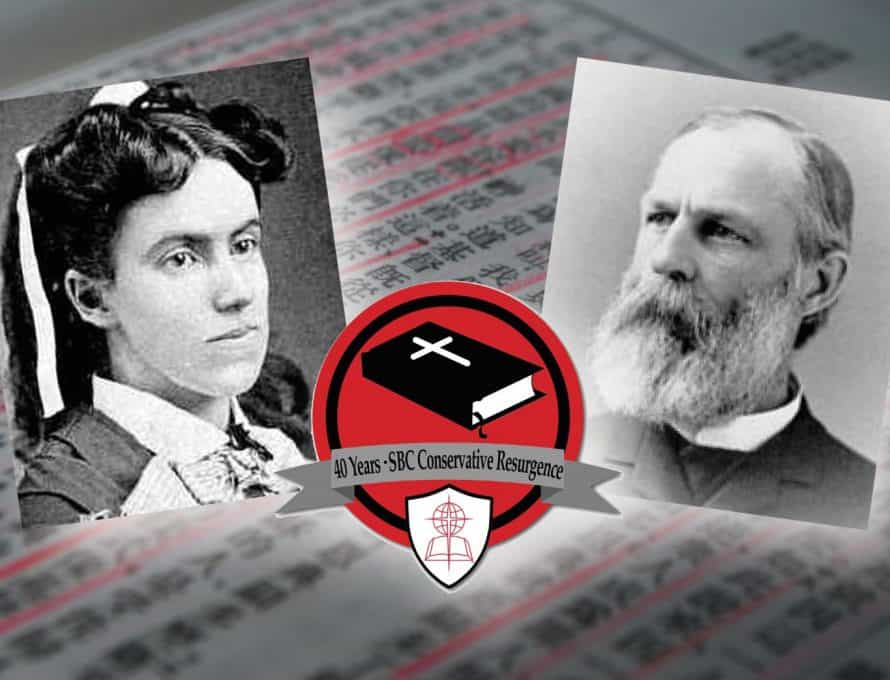

The young lady was none other than Lottie Moon, who beginning in 1873 spent 40 years sharing the gospel among the people of China. Today, she is counted among the most famous of Southern Baptist missionaries, and her devotion to the cause of Christ around the world is celebrated each year through the SBC’s Lottie Moon Christmas Offering for International Missions.

For decades, the famed missionary corresponded with her supposed fiancé, Crawford H. Toy. In fact, Toy may have asked for her hand in marriage once before, but Moon sensed God’s call to serve in China and refused the offer. Yet, writing from China on September 1881, Moon shared that she planned to leave the mission field to “take the professor of Hebrew’s chair at Harvard University in connection with Dr. Toy.” In short, she intended to marry Toy, and she asked her family to prepare for a spring wedding the following year.

But the wedding never came, and Moon remained alone in China until her death in 1912. Later in life, when asked if she had ever been in love, she replied, “Yes, but God had first claim on my life, and since the two conflicted, there could be no question about the result.”

Indeed, by 1882, Toy made it clear that his own beliefs conflicted deeply with the gospel message that Moon devoted her life to proclaiming in China.

Like Moon, Toy once considered missionary service. Indeed, in June 1860, he was appointed by the Foreign Mission Board to serve in Japan, but his plans were frustrated by the outbreak of the Civil War. After the war, he didn’t renew this commitment. Instead, in 1866, he set sail for Germany to study at the University of Berlin. In the end, this decision would cost him not only his relationship with Lottie Moon, but also his Christian faith.

Throughout the 19th century, many German universities and churches had abandoned orthodox Christianity. By 1887, in his first essay about the “downgrade” of biblical Christianity among British Baptists, the famed preacher C. H. Spurgeon declared, “Germany was made unbelieving by her preachers, and England is following in her track.” He criticized the liberal theology and higher critical scholarship that questioned the truthfulness of Scripture.

“A new religion has been initiated, which is no more Christianity than chalk is cheese,” Spurgeon wrote about these “modernist” teachings. “[A]nd this religion, being destitute of moral honesty, palms itself off as the old faith with slight improvements, and on this plea usurps pulpits which were erected for gospel preaching. The Atonement is scouted, the inspiration of Scripture is derided, the Holy Spirit is degraded into an influence, the punishment of sin is turned into fiction, and the resurrection into a myth….”

When Toy returned to the United States in 1868, no one expected that he was slowly abandoning the true faith for this “modernist” imitation. In fact, in 1869, James Petigru Boyce – the founding president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Ky. – invited Toy to join the seminary’s faculty, dubbing him the school’s “shining pearl of learning.”

But only a decade later, Toy’s increasingly liberal theology stirred conflict in the SBC, leading to his dismissal from the school in 1879. In turn, Harvard University President Charles William Eliot invited Toy to join Harvard’s faculty, proudly calling him an “American heretic, whose views on Isaiah had offended the Baptist communion to which he belonged.”

If anyone could doubt the truth of the Harvard president’s claim, they no longer could do so after 1882, when Toy published a Sunday School guide, The History of The Religion of Israel: An Old Testament Primer, for the Unitarian Sunday School Society. In this book, Toy listed “so many historical errors” in Scripture “that some Unitarians threatened to withdraw from the Unitarian union,” according to church historian Gregory Wills.

“The story in Exodus (chapters ii-xiv) tells us of the event as pious Israelites long afterwards thought of it, but we cannot be sure that their recollection was correct,” Toy wrote in one section of his book. “Many of the particulars given in the narrative are improbable.”

According to Toy, the Patriarchs of Israel – Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob – were mere legends, and Moses wasn’t the author of the first five books of the Old Testament. In fact, he argued, Moses was a polytheist, and he didn’t even give the 10 Commandments to the people of Israel.

Toy’s book confirmed the wisdom in Southern Seminary’s decision to dismiss him and in Lottie Moon’s decision to break her engagement with him.

By the time of his death in 1919, Toy no longer attended a Southern Baptist church. In fact, he abandoned the Christian faith completely. Mere pragmatism replaced his former confidence in Scripture.

“Toy is only the best known of the Southern Baptist leaders of the time who embraced a modernist view of the Bible,” according to Wills, professor of church history at Southern Seminary. Indeed, in the early twentieth century, W.O. Carver – a Southern Seminary professor from 1898-1943 who was himself an evolutionist and, reportedly, a “salty old liberal” – testified to the widespread growth of liberalism in the seminary during the decades that followed Toy’s dismissal. Although Toy himself had been dismissed for promoting liberalism in his own day, Carver claimed that such “views would today not be regarded as sufficiently revolutionary to call for drastic action.”

By the 1950s and 1960s, the institutions of the Southern Baptist Convention had been thoroughly infiltrated by leaders who – like Toy before them – questioned the complete inerrancy and infallibility of Scripture. Yet, in those decades, Southern Baptist churches began to call for drastic action – lest their denomination abandon the faith altogether.