WAKE FOREST, N.C. (BP) — Reprinting a theology book by a former slave “offers a window” into the “underexplored vista” of African-American theology, says the Southern Baptist Convention officer who has rediscovered the work.

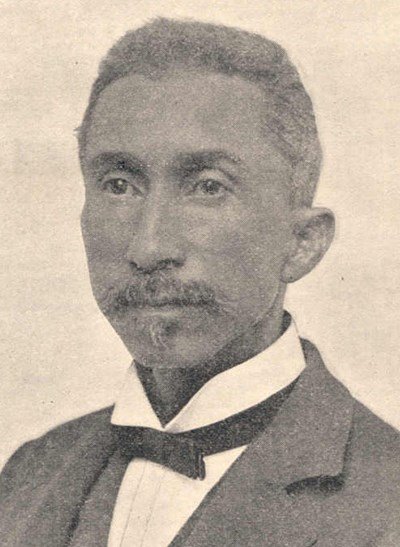

Originally published in 1890 by Charles Octavius Boothe, “Plain Theology for Plain People” was reprinted last year by Lexham Press at the prompting of Walter Strickland, SBC first vice president and associate vice president for Kingdom diversity initiatives at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary.

“African-American theological heritage is a mystery to many because the sources that comprise the tradition are limited,” Strickland, who is African-American, told Baptist Press via email. “Sources are scarce because historically black Christianity is a largely oral tradition and the written resources that have been produced have been obscured because of racial bias.

“Booth’s work is important today because it positions black evangelicals in the broad spectrum of the evangelical tradition,” Strickland said.

In a preface to “Plain Theology for Plain People,” Boothe noted that all the theology books in his day “supposed some educational attainment in their readers” and seemed unsuitable for laypeople and emerging leaders in churches. His book attempted to explain “the doctrines of our holy religion” with “simplicity of arrangement and simplicity of language.”

In less than 150 pages, Boothe explained the doctrines of God, man, salvation, Christ, the Bible, the church and more from a distinctly Baptist and moderately Calvinistic perspective. The work quoted Scripture extensively in addition to journalists of the day, Shakespeare and contemporary theologians like J.M. Frost, who founded the SBC’s Sunday School Board (now LifeWay Christian Resources) in 1891.

Boothe presented defenses of doctrines like believer’s baptism by immersion, perseverance of all true believers and salvation by faith alone. Yet other Bible doctrines, he wrote, are more mysterious and must be believed without full explanation from God.

“We should have thought it strange,” Boothe wrote, “if Mary and Martha, or the centurion of Capernaum, or the widow of Nain, had troubled Jesus with questions as to how he had brought their dead back to life again. It was enough to know that their loved ones lived once more, but it was by no means necessary to know how he had raised them to life again.

“… So those who are raised from spiritual death and made partakers of spiritual life, should not spend any moments of that new life in asking useless questions, but rather busy themselves with devout thanks for the gift, and in earnest efforts to make the most of their life for the glory of the gracious Giver,” Boothe wrote.

Born an Alabama slave in 1845, Boothe learned to read beginning at age 3 and was taught by “several teachers who boarded at the estate where he was enslaved,” Strickland wrote in an introduction to the book. Boothe professed faith in Christ in 1865 and went on to establish and pastor two churches following the Civil War: First Colored Baptist Church in Meridian, Miss., and Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Ala., where civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. pastored in the mid-20th century.

Boothe died in Detroit in 1924.

“Interracial cooperation,” including collaboration with Southern Baptists, Strickland told BP, was “a trademark of Boothe’s life and ministry despite his most fruitful years coinciding with the onset of Jim Crow segregation and the height of lynching terror.”

Strickland hopes Southern Baptists will read Boothe’s work and capture something of his “passion for racial reconciliation.” He also hopes Boothe will help modern readers achieve greater understanding of African-Americans’ importance in “the formation of evangelical thought.”

“Boothe offers a window into an underexplored vista of theological expression, and offers black evangelicals a deep sense of belonging in a tradition that has historically overlooked their voice,” Strickland said. “… The reprint of ‘Plain Theology for Plain People’ is indicative of progress among evangelicals to engage theological voices that affirm unity in Christ yet demonstrating an openness to sharpen each other in the theological task.”