NASHVILLE (BP) — Discussions among Southern Baptist seminary professors about the importance of the biblical languages is nothing new.

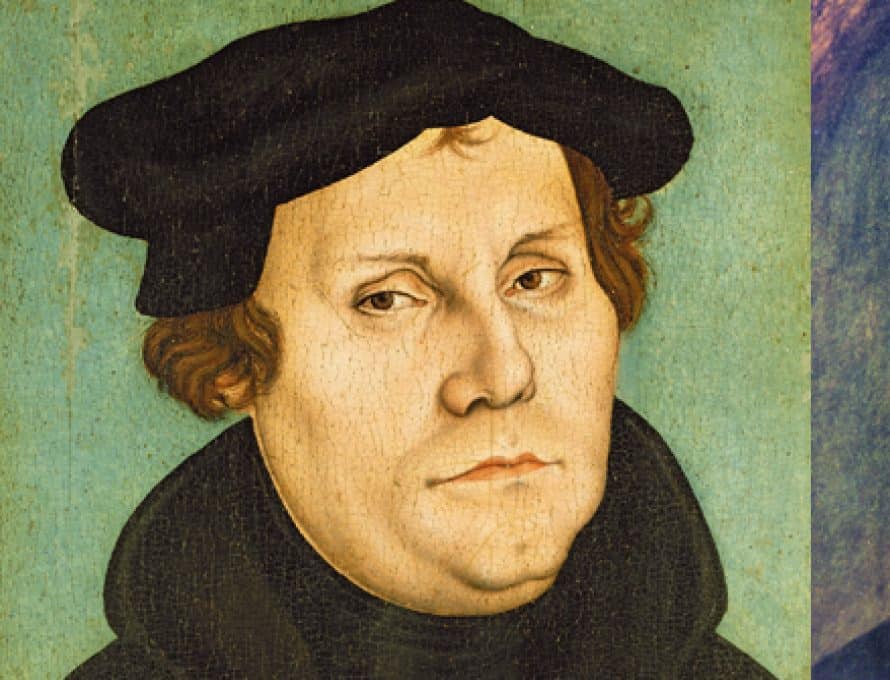

In fact, it’s simply the continuation of a conversation that began well before the Reformation era. Lively interest in the biblical languages — that is, Greek and Hebrew — was “in the air” when Martin Luther called for the reform of the church 500 years ago, noted Timothy George, dean of the Beeson Divinity School at Samford University in Birmingham, Ala.

Luther wrote in 1524, “Let us be sure of this: we will not long preserve the gospel without the languages.”

“The languages are the sheath in which this sword of the Spirit [Eph. 6:17] is contained; they are the casket in which this jewel is enshrined; they are the vessel in which this wine is held; they are the larder in which this food is stored,” he wrote.

Luther wasn’t alone among the Reformers in promoting the study of Greek and Hebrew. In Switzerland, Ulrich Zwingli set up workshops where preachers could practice their exposition of the Bible from the original languages. In Geneva, John Calvin included Greek and Hebrew in the core curriculum for the academy he established in 1559. His predecessor at the academy, Theodore Beza, was “one of the greatest Greek scholars of the 16th century,” George said.

“The revival of both Greek and Hebrew was a new thing at the time of the Reformation,” George told Baptist Press. “It had been brought about through what we call the Renaissance or the rise of humanism.”

The Reformers immediately latched onto critical editions of the Greek and Hebrew texts of the Bible, which were edited and published by these humanists, George explained.

Writing in the preface to his famous 1516 critical edition of the Greek New Testament, the humanist Desiderius Erasmus declared the value of Scripture: “These writings bring you … the speaking, healing, dying, rising Christ Himself, and thus they render Him so fully present that you would see less if you gazed upon Him with your eyes.”

Many Anabaptists and early English Baptists couldn’t read Greek or Hebrew, since they usually came from lower classes of society and hadn’t received formal educations. Nevertheless, they benefitted from Reformation Bible translations based on humanist editions of the Greek New Testament and Hebrew Old Testament.

“The work of translation wasn’t tangential to the Reformation, but it was at the very heart of it,” Jason Lee, dean of the school of biblical and theological studies at Cedarville University in Ohio, told BP. By providing vernacular translations, he added, the Reformers weren’t trying to separate the common folk from Scripture in the original languages.

English Reformer and Bible translator William Tyndale, for example, labored to give his countrymen an English version of the New Testament that closely reflected the Greek text. Writing in the preface to his 1534 revision of the English New Testament, he described how he “compared” his earlier translation to the Greek, weeding “out of it many faults, which lack of help at the beginning, and oversight, did sow therein.” He hesitated to stray from the original Greek even when doing so would clarify the meaning of a passage; instead, where explanation was needed, he added a brief comment in the margin.

Like other Reformers, Tyndale’s goal was to give people “closer access to the original languages, though now through the vernacular translation,” Lee said.

Luther and other Reformers had reasons for such a strong appeal to the original languages. Throughout the Middle Ages, most Christians in Western Europe had no knowledge of Greek or Hebrew. Instead, they based their religious beliefs on a Latin translation called the Vulgate. And some poorly translated passages in the Vulgate were used to support the very practices and beliefs that the Reformers’ protested.

“You see an example of that in the very first of the 95 Theses,” George said. In an act that is often considered today as the starting point of the Reformation, Luther posted his 95 Theses on the door of the castle church in Wittenberg, Germany, on Oct. 31, 1517.

In the first of his theses, Luther wrote, “When our Lord and Master Jesus Christ said, ‘Repent’ [Matt. 4:17], he willed the entire life of believers to be one of repentance.” Here, he took issue with the wording of Matthew 4:17 in the Vulgate, which translated a Greek term meaning “repent” (“metanoeo”) with a Latin word meaning, “do penance.”

“Penance was a part of the sacrament of confession in the Middle Ages,” George explained. “It involved doing certain things: Go on pilgrimage. Say 100 ‘Our Fathers.’ Do a good, charitable deed. It all became part of what Luther called works-righteousness.” But with the Greek New Testament in hand, Luther knew that the Bible didn’t call people to “do some work to merit God’s favor, but rather to have a change of heart.

“So this impacted his whole understanding of salvation, of justification by faith and of the grace of God.”