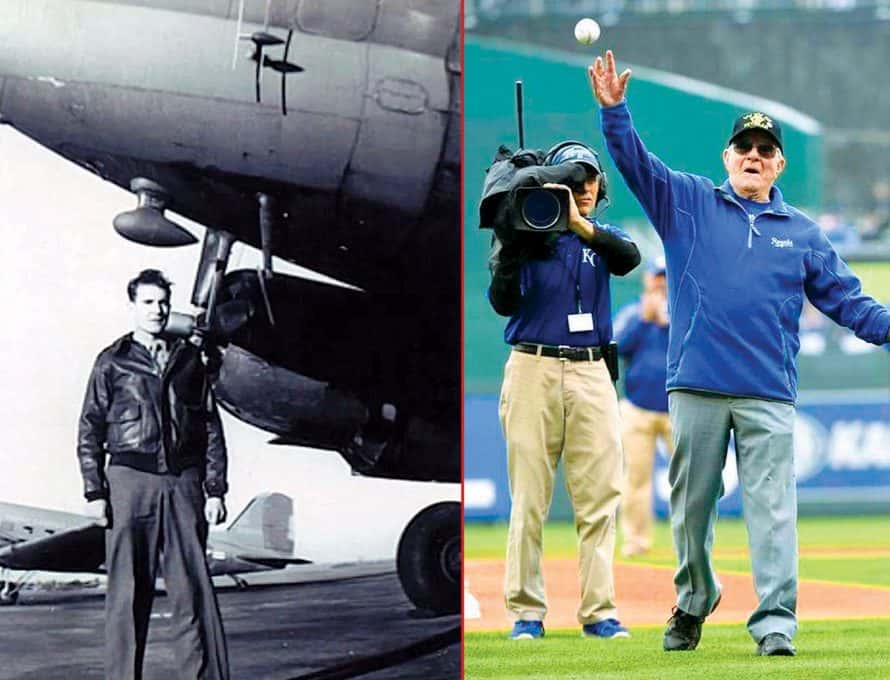

BETHANY – Dale Mitchell took the mound at Kauffman Stadium in front 40,085 roaring fans. Opening Day, 2015: The defending American League Champion Kansas City Royals vs. the Chicago White Sox. Squinting through sunglasses, his cap pulled low, Mitchell cocked his arm back and let his pitch fly.

If you don’t remember Mitchell’s name from the KC starting rotation, it’s because at 90 years old, Mitchell had the honor of throwing out the ceremonial first pitch at Kauffman Stadium for the Royals’ home opener. A former high school second baseman, he and a grandson practiced the pitch on Easter and the next day it was the Royals’ star third baseman, Mike Moustakas who was on the receiving end.

“I wasn’t nervous. I knew I was throwing it to a young guy,” Mitchell, a member of First Baptist, Bethany, said. “I knew he’d run after it if he needed to. I told my Legion and my VFW posts that I hoped I represented them well.”

From his fellow veterans to his church in Bethany to his family (they nominated him for the Buck O’Neal Legacy Seat at Kauffman only to see him throw out the first pitch instead), it’s hard to imagine anyone not being proud of Mitchell. Most of the heroes that sacrifice their youth and lives for their country never get the recognition they deserve. Mitchell got that recognition, but it came 70 years after his B-17 was shot down over Austria.

Nearly 80 years ago, Mitchell accepted Christ at a little country Baptist church when he was 12 years old.

“I was a Christian all during my military service,” he said. “Being with the Lord, I can honestly say I never had any fear during any of it.”

Mitchell graduated high school in 1943. Saying he wanted a challenge and was not afraid of heights, he said goodbye to his high school sweetheart, Doris, and joined the U.S. Army Air Force. After boot camp, he was assigned to be the bottom turret gunner in a B-17 Flying Fortress. Inside the transparent bubble, Staff Sergeant Mitchell would man twin .50 caliber machine guns to defend the bomber from German interceptors.

“We had excellent gunner’s sights,” he said. “You just lined it up.”

His job was easy, Mitchell said, and he and his crewmates were well-trained. But the Flying Fortress’s 13 machine guns were no defense against well-aimed anti-aircraft fire. Mitchell and his crew found this out on an unusually warm winter day after they dropped their 8,000 pounds of bombs on railroad marshalling yards in Vienna, Austria. They took heavy anti-aircraft fire coming in, and even heavier fire as they winged their way back to Italy. It was Mitchell’s fifth bombing run of the war.

“Every time we went on a mission, the chaplain came out and prayed with us,” he said. “I wasn’t afraid for our safety or our success. They always told us that if we made through five missions, we had paid for our training. See, by that time we had pretty well taken control of the sky. The Germans never challenged us much with their planes, but they had pulled back all their anti-aircraft guns from all the countries they’d been run out of into and put them all in German and Austria. And golly, they just let us have it.”

The B-17 took hits to its engine and fuel tanks and caught fire as they neared the Yugoslavian border. The navigator kept telling the crew that if they could just keep the plane in the air 15-20 more minutes, they would be able to bail out knowing they’d be returned to the Americans a day or two later.

“I guess we almost made it through that fifth mission,” Mitchell said. “If we hadn’t caught on fire, we would have made it back to Italy.”

The pilot stayed with the plane the longest as everyone else bailed out. While the pilot made it close enough to the border that he was picked up by friendly forces, seven of the crew – including Mitchell – were less fortunate as they bailed out.

“I lit right in the middle of a Hitler Youth school,” he said. “Right on the lawn in front of the whole class.”

They were taken by train to a camp near Berlin, and it was on the way Mitchell said he had his only true moment of fear during the war, the only time he “cried out to God,” sure he was going to die. It was a case of friendly fire.

“Our Air Force attacked the German train I was on,” Mitchell said. “I thought death was certain, and I cried out to God to take me to Heaven.”

Death wasn’t certain then, but surviving as a prisoner of war (POW) wasn’t certain either. Soon he and others were transferred to Stalag VII-A near Moosberg, the largest German POW camp. Instead of transfer by train, Mitchell and thousands of others were forced to march the 300 miles to the new camp.

“Everyone knew that Germany had lost the war, so we were treated much better than the POWs that were captured earlier,” he said. “We slept on the ground rolled up in a blanket. There was just one tap for water, and the line never went down, day or night. We never faulted the Germans much for not giving us food, because they didn’t have any food either. I was blessed to stay healthy. I was young and grew up on the farm. I guess I handled it well.”

Four months later, on April 29, 1945, Patton’s Third Army rolled through Bavaria in their Sherman tanks and liberated the camp, setting Mitchell and 110,000 other Allied prisoners at Stalag VII-A free.

Once home, Mitchell married Doris and graduated from the University of Missouri’s agriculture school in 1949. He worked for the U.S. Soil Conservation Service until he retired 30 years ago.

Seventy years removed from war, Mitchell now enjoys time with Doris and the four generations of his family, worshipping at First Baptist, and cheering the Royals in their recent resurgence – though it is usually from the comfort of his own home instead of the pitcher’s mound.

Almost as if he was looking down his sights, Mitchell’s pitch on Opening Day flew straight, and one-hopped to the plate and into his target, Moustakas’s glove. The crowd cheered even louder.

For the rest of the opener, Mitchell handed the pitching duties off to Kansas City’s ace Yordano Ventura. The Royals won the April 6 game against the White Sox 10-1.